The Strikes That Came Before - Part 2

Where Is Hollywood Going?

Thanks for reading Two-Hats Television! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Click here for part 1 of my history of Hollywood labour movements.

Only nineteen years after that 154 day strike in 1988, the WGA prepared to strike again. Their 2007 strike was just sixteen years ago. These picket lines are steadily moving closer and closer together. The way we consume media is changing ever more rapidly, and with that change comes a need for industrial action.

Before The Strike

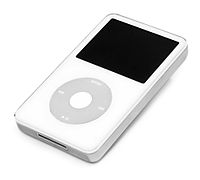

In October 2005, Apple introduced iTunes 6. For the first time, customers could purchase and view video content directly from the iTunes store. Apple also released the 5th generation iPod - the first iPod capable of playing video. ABC was the first major American network to strike a deal with Apple. The network began to release episodes of new shows like Desperate Housewives and Lost directly on iTunes. By the end of the year, NBC had followed suit after seeing the ratings increase the deal had created for ABC.

The idea was simple. Just as the songs in the iTunes store all cost $0.99, so every episode of television available on iTunes would cost $1.99 - a bargain way to test out a show on your own time before committing an hour a week to Lost. Attaining the rights to distribute a television show involved navigating a complicated mess of relationships between networks, production studios and various other affiliates, and there was no precedent set for this new method of distribution. At the time NBC made their deal with Apple, Steve Job told the New York Times that consumer demand would resolve these conflicts, saying that “People forget we all work for the viewers, and consumers are demanding different services and options.” The increased demand for television on the viewers’ terms had all of the networks looking for new ways to release television, especially online avenues. The previous few years had seen a huge increase in piracy - downloading a show wasn’t just cheap, but a more convenient way to watch television than committing to that hour a week. Much as iTunes came about as a response to sites like Napster (for more on the rise and fall of Napster, I highly recommend this episode of You’re Wrong About), now television needed to become “legitimately” available online.

There was just one problem. In all the excitement of a new world of online distribution, certain groups hadn’t come into consideration. Including, of course, the writers.

The 2007 Strike

I should note, at this point, that a lot of the information about the 2007 WGA strike in this article came from this excellent piece published in the Hollywood Reporter in 2018. My favourite anecdote in the piece comes from Damon Lindelof. He remembers walking past an Apple storefront in 2006 and being delighted by the advertising for his show Lost plastered all over the shop. Then, the realisation hit. People were paying $1.99 an episode of his show and neither he, nor the rest of the writers room, were seeing a penny of it.

Every three years, the WGA negotiates a basic contract with the AMPTP (Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers). It’s called the Minimum Basic Agreement, or MBA. In 2007, when the new MBA was being negotiated, the WGA were focused on new media models and how, exactly, writers would get paid for work released online. Alongside that, writers were looking for a more sensible share of the DVD market - while DVDs were technically covered by previous home video agreements, they had since become a much bigger part of the overall entertainment business - as well as better protections for those working in animation and reality television. The big players in the AMPTP at the time included Les Moonves (CEO of CBS), Jeff Zucker (CEO of NBC and very much the bad guy in my upcoming book Friends, a Golden Age of the Sitcom), Harvey Weinstein (yup) and Bob Iger (a familiar name to Disney fans). The AMPTP wanted to wait three years, until the next MBA, to see how all this online stuff would pan out. The WGA had been burned before in negotiations over new media models, and weren’t willing to wait.

Unlike previous writers strikes, this time showrunners were willing to step up. Showrunner, in the American television industry, is a shorthand term for a writer-producer combo. During previous strikes and work stoppages, showrunners had often continued on with production duties. This time, the WGA wanted to keep the strike short, and working showrunners committed to staying off set for the duration. On November 2nd, after 3 months of negotiations, the WGA announced that its members would strike if a deal with the AMPTP wasn’t reached by midnight, November 4th. On the 5th of November (insert your own “remember remember” joke here) the strikes began. Greg Daniels, showrunner of The Office, was one of the very first people on the picket lines, largely because he had to get to set at four in the morning to stop the caterers from coming in. NBC tried to insist that The Office continue filming, as the next episode in the season - “Dinner Party” - was already written and ready to go. Steve Carell, however, refused to cross the picket lines.

With showrunners stepping away from work along with the writers, production came to a halt across film and television. No one wanted this strike to drag on, but in December 2007 talks between the WGA and the AMPTP broke down. The AMPTP walked away, issuing a press release stating that they wouldn’t return to negotiations until certain proposals, mostly those concerning animation and reality television, had come off the table. The WGA responded in good faith, bringing in outside counsel, but this was just a delaying tactic for the AMPTP.

January 14th 2007 became known as Hollywood’s “Black Monday”. Major studios shut down over forty writer-producer deals, citing the “force majeure” clause that allowed them to break contracts in the wake of an unforeseeable event. The studios needed the strike to last at least ninety days to enact the clause. Dragging the strike out to January gave the studios enough justification to break those contracts, and it put the WGA on the back foot as more and more guild members pushed for a swift end to the strike.

At this point, the DGA (Directors Guild of America) were beginning their own negotiations with the AMPTP. There was a group of writers nicknamed “The Dirty Thirty” that wanted to release a statement demanding that the WGA accept whatever deal the DGA got, while another splinter group named “The WD-40” tried to convince the DGA to delay negotiations until the WGA strike was resolved.

On January 17th 2008, the DGA signed their deal with the AMPTP. The WGA’s bargaining strength was seriously weakened. The DGA had negotiated better residuals for television shows sold online, extended union contracts for web shows, and compensation for shows that were streamed free online on as-supported websites. It wasn’t an ideal agreement, however. The compensation for shows made available online only began after a certain time period. The LA Times explained at the time that ”Studios would get a 17-day window for existing shows and 24 days on new series. The concern is that most viewers watch reruns of their favorite shows online within days after the initial broadcast -- not weeks -- giving studios little incentive to run a program beyond the promotional window.”

100 days after the strike began, on February 12th, over 90% of the WGA voted to end the strike. On February 26th, the WGA approved a new three-year contract with the AMPTP. Thanks to that contract, there were rules in place about streamers hiring WGA writers before Netflix was anything more than a DVD rental service. Largely though, the WGA accepted the same deal as the DGA.

The Immediate Aftermath

The 2007 strike has been blamed for many things. Not only did it destroy previously good seasons of television, but as trouble began brewing with the WGA this year, more and more people pointed the finger at the previous strike for the rise of reality television. In fact, reality television began to take over before iTunes 6 was even a twinkle in Steve Jobs’ eye. It was seven years previous, in 2000, when Survivor became the first reality show to reach the #1 spot in the season’s ratings. In truth, reality television was so huge by 2007 that The Apprentice had already become an unfortunate fixture in NBC’s “Must See” Thursday line up - a two hour programming block that had been the territory of sitcoms alone for over a decade.

While the 2007 strike didn’t cause the rise in reality, that easy availability of unscripted programming was what gave networks the confidence to drag things out. Before, those networks might have faced glaring gaps in the schedules and a huge loss in ad revenue as they turned to re-runs to plug them, now another season of American Idol could fill the space created by writers on picket lines.

The WGA, in negotiations, were pushing for more rights for those working in reality television, arguing that those producers shaping scenarios and creating narratives out of raw footage deserve to be protected as writers. In 2006, WGA West even attempted to organise employees of America’s Next Top Model. Those employees voted to join the WGA, and were swiftly fired and replaced. It was those necessary provisions for reality television that the WGA took off the table after the AMPTP walked away from negotiations in December 2007. Eventually, they landed back on the table, and thanks to the WGA you’ll now see credits like “Story Producer” in some of your favourite reality shows.

The biggest impact that the 2007 strike had was on network television. Binge watch almost any show that aired in the aughts, and you’ll find an odd little season with half as many episodes as the rest and a disappointing finale - the strike season. The eventual crash and burn of Heroes came after the strike cut the second season in half, taking out an entire storyline. Lost lost the chance to establish any kind of backstory for new characters. Scrubs nearly ended for good on a parody of The Princess Bride, before ABC reclaimed the show from NBC and gave it one more season. (Technically, two more seasons, but we don’t talk about season nine of Scrubs. Not ever.) Pushing Daisies, the weird little Bryan Fuller (Hannibal, American Gods) show starring Lee Pace as a pie-maker who could resurrect the de3ad, ended up on hiatus after ten months and, as a result, struggled to find its audience, instead becoming a cult classic that ended too soon.

The 2007 strike created some, though not enough, protection for writers as television moved online. It led to a strange year of television. It might lead to the WGA breaking their record for the longest strike in guild history. It certainly led to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA striking together now, for the first time in sixty years.

Where are we now?

This year, on May 1st, the current MBA the WGA had with the AMPTP expired. The strike began on May 2nd. Some companies had learned lessons from the previous strike - showrunners were now contracted to continue working as producers, even if their writer side wanted to walk the picket line. On May 3rd, Disney was the first studio to insist that all showrunners, and anyone who fell under the writer-producer hyphenate, would still have to perform their non-writing duties. If you were wondering why season 2 of Andor remained in production after the WGA went on strike, then know it wasn’t down to Tony Gilroy voluntarily crossing picket lines.

In July, Deadline reported that the AMPTP planned on dragging out negotiations until at least late October, in the hopes of quite literally starving the writers out. On July 14th, SAG-AFTRA joined the strike. Both unions are negotiating over the same issues. Technology has changed again. This time, it’s fair residuals for streaming and restrictions on the use of A.I. that the AMPTP are refusing to negotiate over. At the time of writing, negotiations have continued, but in poor faith. The AMPTP have barely engaged in what both the writers and actors are asking for.

Unlike the last combined strike, this time both unions working together has created much more work stoppage. This is especially true when it comes to promotion. With the actors staying away from red carpets, and with online influences now covered by SAG-AFTRA, the big names aren’t around to promote their movies and there’s a lot less organic social media content to go with them. Barbie got out just in time. A lot of releases are being delayed until next year, with one of the most recent announcements being that the sequel to Dune won’t be coming out in 2023. The Primetime Emmy Awards (already unpopular for a series of truly odd nominations this year) have been pushed to January, in the hopes that some of the nominees might be willing to show up by then. The work stoppages mean that there’ll be another huge disruption to the (admittedly less relevant in the streaming era) network television season. Even shows like Good Omens have been released with distinctly dodgy subtitles, as there’s no writers handy to correct them.

The longer-term impact will be broader. It’s going to be more than just one weird season of television. More and more shows will be cancelled, contracts will be terminated and eventually content will dry up without an agreement between the guilds and the AMPTP. This strike is bigger than any before, and it’s hitting the industry harder. Now, as well as SAG-AFTRA and the WGA striking together, SAG-AFTRA may also be going on a simultaneous strike against the major players in the video game industry over, you guessed it, fair use of A.I.

Industrial action being required in the entertainment industry to keep workers safe and fairly compensated as technology grows is nothing new. It’s depressingly repetitive. It should not take a strike to get writers and actors fairly paid. These strikes are not about keeping the wealthy in their mansions, they’re about creative people being able to pay for rent, food and health insurance. They’re about quality. Asking the Chat GPT to create a Seinfeld episode might make for a surrealist masterpiece once, but the next Seinfeld (or insert preferred sitcom here) is living in the head of someone who deserves to be paid fairly for their work.

Hollywood got here through stubbornness, greed and growth. As for where it goes from here? That’s anyone’s guess.

Thanks for reading Two-Hats Television! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.